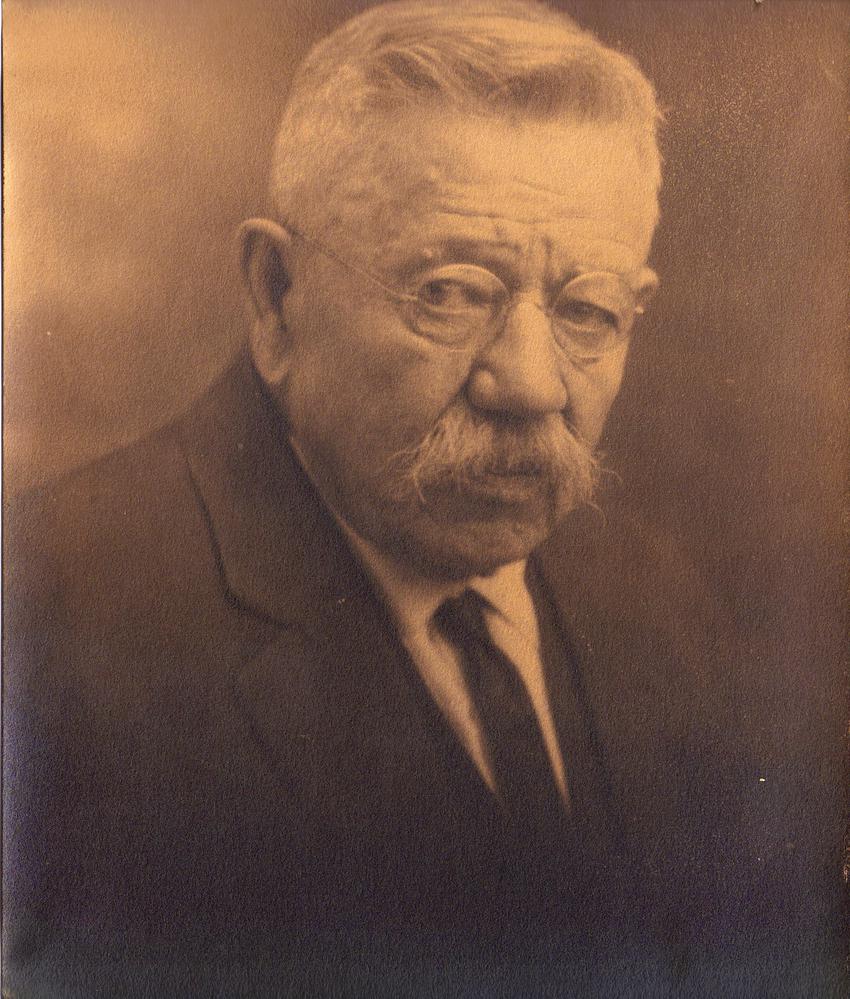

John Rachač

John Rachac

by John Sielaff

Among the many fine historic buildings in St. Paul, two of my favorites are the State Capitol, built between 1895 and 1905, and the James J. Hill mansion on Summit Avenue, which was finished in 1891. The names of the architects of these buildings are well known and the craftsmanship of those who actually did the work is generally admired, but the names of the workers have been forgotten. Using hand tools, with skills for the most part not practiced by today’s construction trades workers, these structures were made by an anonymous, primarily immigrant, workforce. A Czech carpenter named John Rachač was one of these men at both the Hill house and the Capitol.

John Rachač, the second child of Jan and Mary Rachač, was born in Mažice, Bohemia (now in the Czech Republic) on April 19, 1848. John’s parents and their seven children immigrated to America in 1863 during the American Civil War. Their ship, the Australia, landed in New York on July 1, 1863 and they immediately got on a train headed west. Their trip, however, was halted for several days in the Philadelphia area due to the battle of Gettysburg, as the rail lines were being used to shuttle troops and the wounded. From Philadelphia, the typical route would have been by rail to Chicago, then to Galena, Illinois, where one could catch a riverboat north to Red Wing or St. Paul. From there they would have had to travel by horse and buggy to Belle Plaine, where the family found a friendly Czech community close to the town of New Prague. Son John was 14 at the time and had already completed 2 years of his apprenticeship in carpentry back in Bohemia. He must have been a welcome addition to the community where everyone needed houses and farm buildings on their recently homesteaded land.

John lived on the farm helping his parents until 1871, when he married Anna Shetka, a fellow Bohemian emigrant. Shortly thereafter, in 1873, at the age of 24, he decided to ply his carpentry skills and raise his family in the growing city of St. Paul. On the farm in Belle Plaine, John Rachač might have had to travel considerable distance to find carpentry work; not a big problem for a single man. In the city, work would be more conveniently located and he could make it home for dinner after the work day.

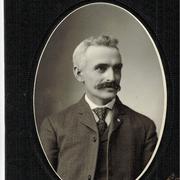

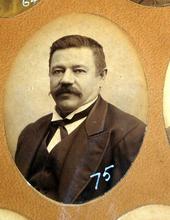

The Rachačs were part of a large influx of Czech immigrants to St. Paul in the 1870’s. So many had settled in the low lying area west of the Upper Levee that it came to be known as Bohemian Flats. As they got jobs, they moved up the hill out of the Mississippi flood plain and into the West End neighborhood, establishing institutions that exist to this day. St. Stanislav Kosta Church, a Catholic parish, was dedicated in 1872. More importantly for John Rachač was a founding member of the C.S.P.S. Lodge Czech No.12, a branch of the Cesko-Slovansky Podporujici Spolek (Czech-Slovak Protective Society) . The C.S.P.S. was a fraternal and beneficial society like many other similar ethnic organizations of that time. Free-thinking Czechs, however, thought of their organization also as an alternative to the religion, whether Catholic or Protestant, that they had left behind in the Old World. The St. Paul C.S.P.S. bought a lot on West 7th St. right next to St. Stanislav and moved an old schoolhouse to the site for their meeting hall in 1879. After this building was destroyed by a fire in 1886, they immediately raised the money to build a brick structure on the same site. This building, with its large addition dating to 1917, is still the center of cultural activities for the Czech community and is the oldest building of its kind in the country. The building housed a literary society and library, Czech singing and theatre groups, as well as the Czech gymnastic organization, Sokol, which still meets there. Rachač was an active member of the C.S.P.S. and his picture is included in pictures of the early members still displayed at the hall.

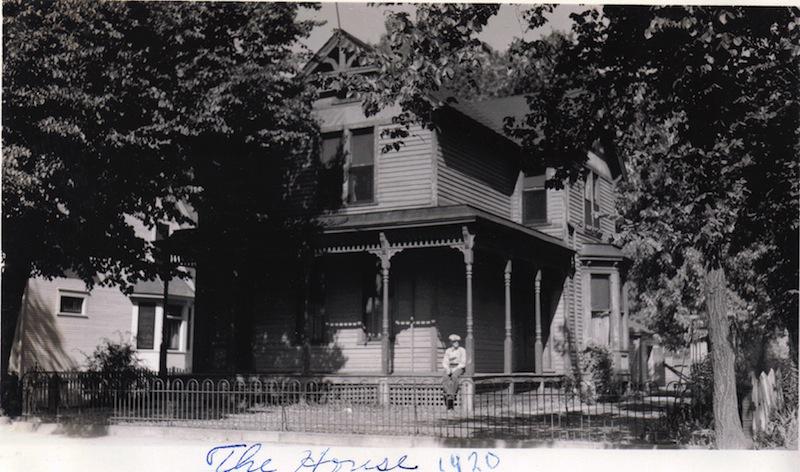

During this period, John and Anna Rachač rented living space on West 7th St. until 1886, when John built the house that still stands at 309 Harrison Avenue, just a few blocks from the C.S.P.S. Hall. This is where they raised their nine children, and many of the kids lived there well into their twenties. The house became the center of activities for the extended family and stayed in the family until 1966. One son, William, also raised his family there while John, after Anna died in 1916, lived in an apartment upstairs.

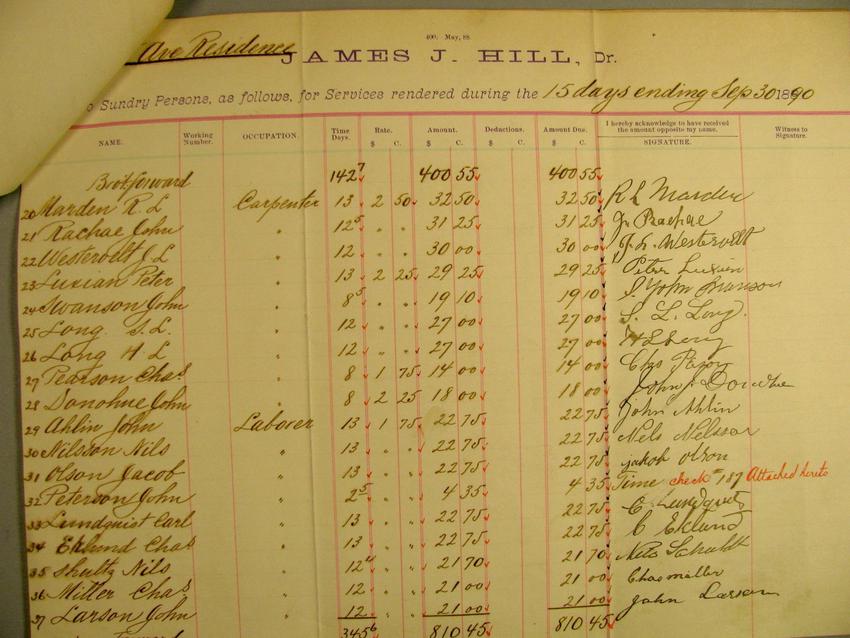

Rachač worked as an independent contractor for the first couple decades of his career in St. Paul. His name appears on building permits as the contractor for several buildings and additions in the West 7th Street neighborhood and many of his clients were fellow members of the C.S.P.S. In addition to his own contracting business, Rachač also hired on to other jobs. Payroll records for the construction of railroad baron James J. Hill’s mansion in 1890 and 1891 list him among the carpenters there. Depending on the weather and the phase of the operation the Hill house employed as few as 2 and as many as 33 carpenters while it was being built. This was the largest and most expensive home built in Minnesota up to the time and included all the latest innovations in technology. For the design of the house, Hill avoided local architects and went with the Boston firm of Peabody and Stearns who had done work for his friends J. P. Morgan and the Vanderbilts. He soon fired Peabody and Stearns, however, paid them for the plans, and had his own man, James Brody, a local architect, manage the construction. He then hired a different Boston architect to do the interior design.

Rachač was first hired in June of 1890 to work on the mansion with a crew of 11 other carpenters and was employed off and on for 5 weeks that year. Because Hill was very concerned about fire prevention, he wanted the structure of the house to be steel and masonry. Most of the carpentry involved the lavish interior millwork and paneling and was done in 1891 when Rachač was there with about 30 other carpenters. One can easily imagine Hill wandering around the job site from time to time. Brody must have been pretty careful about who he had on the job. Although Rachač seems to be the only Czech name among the carpenters at the Hill house, there was a laborer who worked sporadically on the job named Thomas Shetka. Shetka was Anna’s brother, Rachač’s brother in law, and was later hired as the “day fireman”, that is, the one responsible for the heating plant during daylight hours. This was a steady job, unlike the construction work, and Shetka stayed on in this capacity for several years after the completion of the house.

John Rachač was clearly proud of his carpentry at the Hill house. He did not work there during the early stages but was brought in for the finish phase of the project. His family knew about him having worked there and his great granddaughter was able to tour the house with her mother and admire the fine carpentry of her great grandfather. It is not entirely clear if Rachač considered the job very well paying. He, like most of the other carpenters on the job was paid $2.50 for a ten-hour day or 25 cents an hour for any fraction of that. Unskilled laborers like Shetka got $1.75 a day. In 1890, a typical week for a carpenter was six days, ten hours a day, but quite a few weeks, Rachač and many other carpenters worked less, possibly on account of the weather or lack of work, or maybe they had other more lucrative jobs of their own to go to.

In the 1890’s, John made the transition to work on larger construction projects. When he was building homes on his own, he could set his own wages and hours. Now, he would be working for wages for a large contractor with many employees. As a rule, Rachač would give his profession as carpenter in the yearly St. Paul city directory, but would name no employer. However, in 1897 he listed Butler-Ryan as his employer. Unions were flourishing at this time as workers recognized the advantage of banding together to demand better wages and working conditions. Building Trades Unions were also concerned that industrialization was eroding standards of craftsmanship as contractors’ tended to try to get by with the cheapest help. The unions sought to control who could be hired as a journeyman carpenter and new applicants were subject to a vote of the membership. Rachač’s union book indicates that in October 1898, he joined Carpenters’ Union Local 87. Possibly this was when he went to work on the construction of the new State Capitol building. He was a member in good standing for the remainder of his life, long after he had retired, indicating that his union membership was important to him.

The 1880’s saw the first real surge in union organization in St. Paul. The St. Paul Trades and Labor Assembly founded in 1882 encompassed “Trades” unions such as Bricklayers and Printers and “Labor” assemblies of the Knights of Labor. St Paul Local 87 of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners formally organized in January of 1885, but grew out of an earlier Knights of Labor Assembly. The Knights of Labor, a nationwide, all inclusive, progressive organization was popular in 1880’s St. Paul. At one time, the city held 23 different Assembles, as the local chapters were called. Two of the Workingman’s Educational Assembly #2822’s delegates to the St. Paul Trades and Labor were founding members of the Carpenters’ Union in St. Paul. Rachač did not join the union at this time. His membership in the C.S.P.S. probably afforded him the same type of sick and death benefits offered by the union. In addition, Local 87’s meetings were conducted in English creating a barrier for Rachač and other non-English speakers. To remedy this situation, in December of 1885, they ordered 200 copies of the Brotherhood Constitution in German and, by 1887, through their efforts, there were separate locals for German, French and Scandinavian speakers. In June of 1887, these carpenters united to launch the largest strike St. Paul had seen up to this time, demanding a nine-hour day and recognition of the Union by the contractors. The strike got a lot of coverage in the local press and gained momentum as the better organized Bricklayers Union went out in sympathy. Some of the smaller contractors quickly agreed to the demands, but the larger ones were adamantly opposed and the carpenters did not have the funds to conduct a prolonged strike. The Minnesota Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 1888 that three fourths of St. Paul carpenters were still working ten-hour days. In the 1890’s, as the economy contracted, membership dwindled and the ethnic locals were disbanded. By 1893, with the country in a severe economic downturn, the Carpenters’ Union looked like a losing proposition and was down to only a couple dozen members in St. Paul. By 1898 however, when Rachač joined, construction was booming and, with the help of more militant carpenters from Minneapolis, the St. Paul Union demanded and got their first contract with the employers. Between 1897 and 1902 membership had increased from 50 to over 850 members and in 1902 the carpenters, after a short strike, were able to negotiate a contract for an eight-hour day at 37 ½ cents per hour.

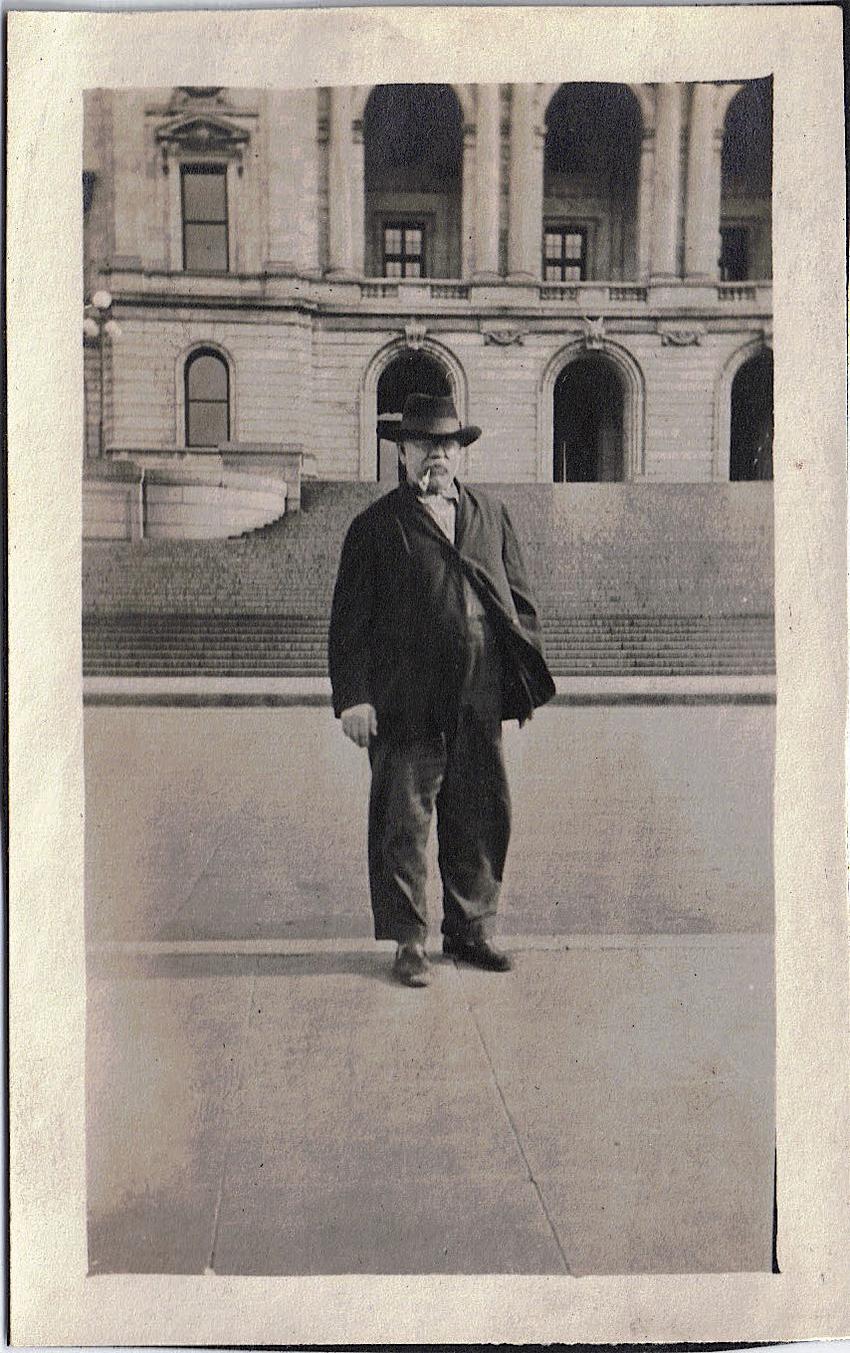

Rachač’s employer, Butler-Ryan, was the contractor for the superstructure and the interior of the Capitol. Construction took place between 1895 and 1905 and was prolonged in large part by the hesitancy of the Minnesota Legislature. Legislation was passed in 1893 for the Governor to appoint a Commission to oversee the construction of a new Capitol, but there was no fixed idea of what the building should look like or cost and the funding, common in the 19th Century, was at first done on a pay as you go system. George Grant Construction of St. Paul won the contract for the foundation and this was finished and paid for in 1896. Then the Capitol Commission had to get the legislature to appropriate funds before they could even invite bids for the next phase. Delay was also caused by the huge controversy over whether the exterior of the building should feature Minnesota stone or use the “foreign-sourced” Georgia marble favored by the architect. Contractors were invited to submit bids using different types of stone and this produced a bewildering array of choices for the Commissioners. Butler-Ryan partner Mike Ryan was intimidated by the complexity and bonding requirements of the project and withdrew from the firm, though Walter Butler and his brothers William, Cooley, John and Emmett were anxious to get the job. The winning bid by the Butler- Ryan Company (which later became Butler Brothers Company) specified a combination of Minnesota granite on the lower part of the building and Georgia marble for the upper two floors and the dome. The Capitol Commission defended their decision to use the out-of-state stone by pointing out that using all granite, being more difficult to work with than marble, would increase costs. In reality, Butler Ryan’s low bid had been based on the estimate of a Georgia marble quarryman who said he would supply marble at 25 cents per cubic foot. It soon become apparent that the price would really be 40 cents, so John Butler went to Georgia, leased a quarry, hired a local crew, and took over the extraction of the stone. Huge 20 ton blocks were loaded onto flat cars and brought by rail to be cut and polished on site. Butler recruited several skilled Southern marble workers, some White, some African-American, who came to St. Paul to work and train locals in finishing the stone.

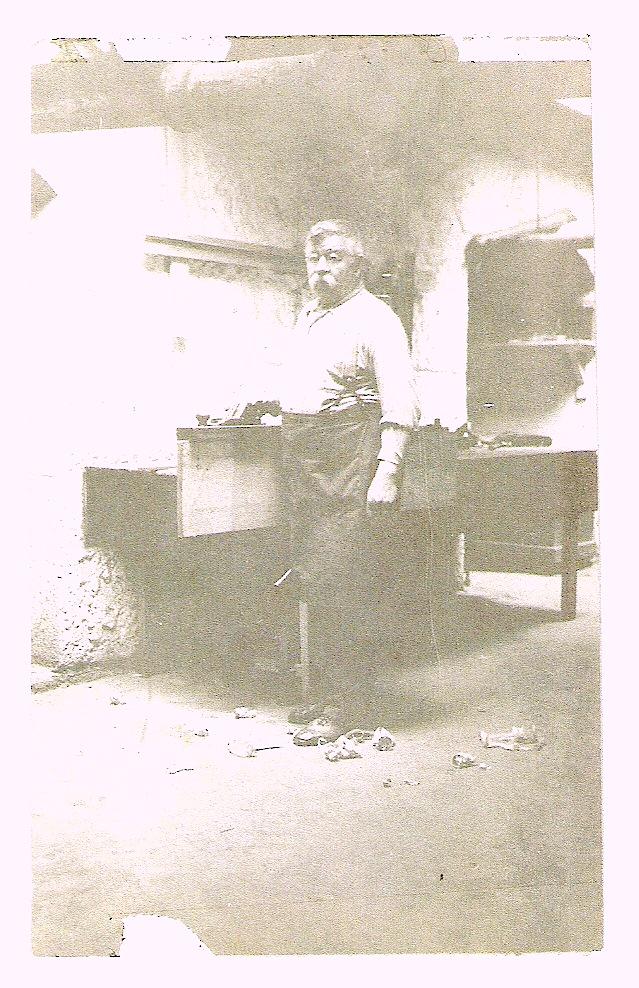

Much of the work that Rachač was familiar with in residential construction would have been unneeded on the stone and steel structure. During the early stages of construction the carpenters were building forms for the concrete footings, wooden false work used to support masonry arches, and the extensive scaffolding needed by the bricklayers and stonemasons. Butler devised a system of huge wooden trestles for the movable cranes used to handle the stone and towers to support work on the domes. In March of 1902 Butler Brothers (successor to Butler-Ryan) got the contract for the interior finish work which included the installation of wood paneling and the interior doors and windows. At that time much of the work on doors and windows was performed on site and many carpenters were employed for this job.

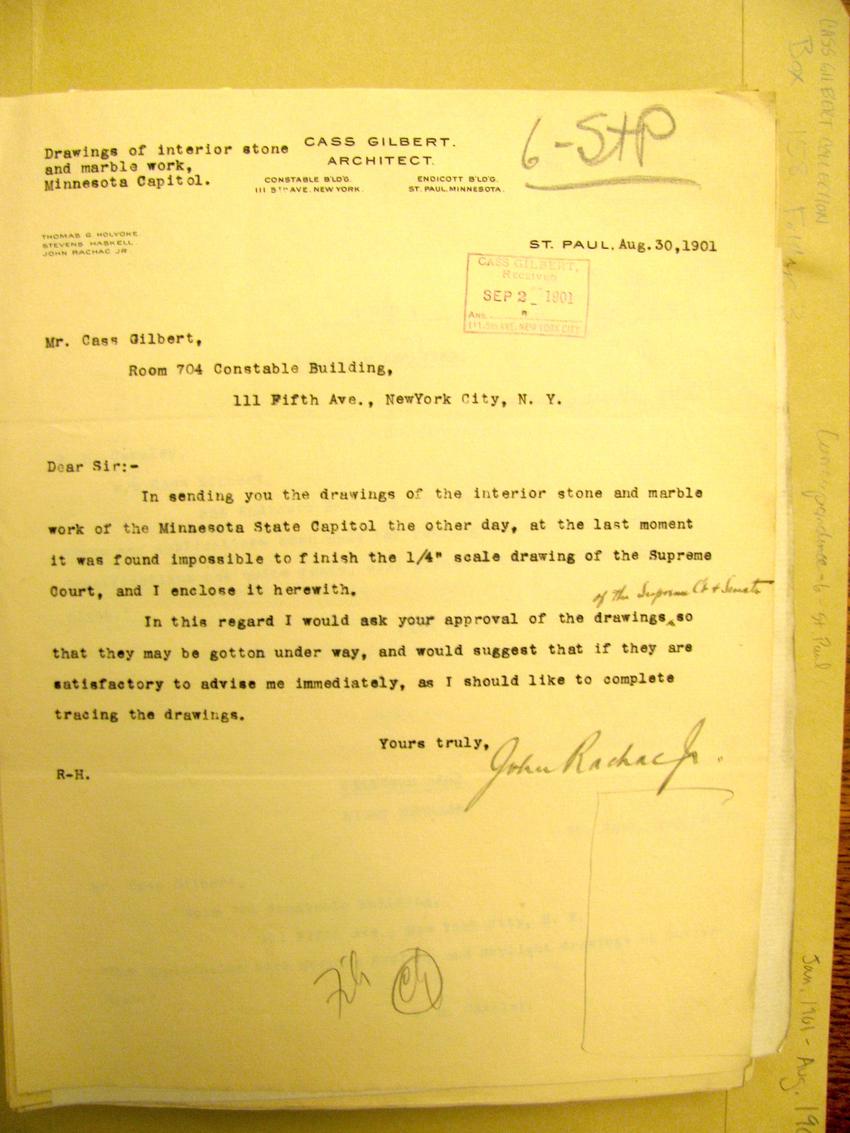

While John Rachač was working at the Capitol construction his oldest son, John Jr., was also involved in the construction industry working as draftsmen in the office of Cass Gilbert, the architect of the Capitol. John Jr., who had won prizes in his last year at St. Paul High School for architectural drafting, had gone to work for the firm of Gilbert and Taylor in 1889 at the age of 16. At the time secondary education was not a necessary requirement for employment in the field. Gilbert himself had studied at M.I.T. for only 9 months before beginning his apprenticeship in New York. The 1880’s were boom years for Gilbert and Taylor, designing homes and churches in St. Paul, and by 1889 the firm was working on its first big commercial contract, the Endicott Building, in downtown St. Paul. The economic downturn of the 1890’s, however, put a halt to the construction industry. Gilbert’s partner, James Taylor, left town to find work elsewhere, and Gilbert carried on alone though on a smaller scale. To build up a client base he joined the Minnesota Club and met James J. Hill there. The same year Rachač Sr. was working on the Hill house, his son was working in Gilbert’s office as the architect was designing the fence, gates and powerhouse for the mansion. This led to Gilbert’s work on the new St. Paul Seminary for Archbishop John Ireland, which Hill financed. But Gilbert found Hill’s imperious attitude demeaning. Once, when they were arguing about the budget for the Seminary job, Hill opened the vault in the new Summit Avenue home to show off a large cache of diamonds and jewels, just to demonstrate who was calling the shots and why. Young Rachač worked for Gilbert through all these years except 1894 when he listed the Public Library as his employer.

During these slim years Gilbert had his eyes on the Capitol job and was positioning himself, knowing this could be the turning point in his career. In 1891, he got on the national board of the American Institute of Architects and in 1894 became the president of the Minnesota chapter. In 1893 Minnesota Governor Knute Nelson appointed a Commission to oversee the construction of a new capitol building and the chairman happened to be an old family friend of Gilbert’s, Channing Seabury. But when the job was put out for bids in 1894, the legislature had imposed several restrictions: a budget cap of 2 million and architects fees of 2 ½ percent. Gilbert had to meet with Seabury to explain that he and most other A.I.A. architects would be boycotting the competition. Although there were 56 entries the Commission judged them all to be inadequate and a second round of bidding was held in 1895 using the recommendations of Gilbert and the A.I.A. which required a higher commission and complete oversight of the construction process by the architect. There were five finalists chosen by the Commission and Gilbert was the eventual victor. The final cost of the project would be 4 ½ million.

John Rachač, Jr. was present at the groundbreaking in 1896, and in 1898, when the cornerstone of the Capitol was set, the Rachač family got a special invitation to the ceremony and John Jr.’s name was included in the list of Gilbert’s associates included in the cornerstone box. Gilbert’s office stationary of these years lists John Rachač as one of the three associates in the firm along with Thomas Holyoke and George Carsley. In May of 1900, the young architect, with financial aid and loans from Gilbert, traveled to Paris to study at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. After he got over his homesickness, he wrote to Gilbert that he really wanted to study there for two more years and get into the upper level classes “where the really big work and design commence.” But Gilbert, who was financing the schooling and keeping Rachač’s job open in St. Paul, instead advised him to tour Italy where he could see firsthand the architecture Gilbert was trying to reproduce in America and come back home by July 1901. Shortly after his return, Rachač demonstrated his proficiency by drawing the plans for the complicated cantilevered oval stairs in the northeast corner of the Capitol building. Gilbert had opened a New York office in 1899 and was spending most of his time there so the responsibilities of those working in the St. Paul office increased. Rachač was kept busy there, as well as traveling to oversee work in St. Louis. Towards the end of the project, he was working on plans that his father would soon execute in the new building. This must have made for some interesting conversations around the Rachač dinner table. Maybe Gilbert was recalling this when, a few years later, he decried new construction practices, “The (general contractors) have been able to force the sub-contractor to a lower price, consequently, they have introduced a lower grade of work, and have succeeded in keeping the architect at arm’s length from the man who does the work….As a rule it should be the sentiment of the architects of the country to deal with the men that do the work.” After the Capitol was completed, John Jr. moved from the family home on Harrison to New York, Americanized his name to John Rockart at Gilbert’s insistence, and worked with Gilbert for 25 more years as the office manager of the firm. Channing Seabury’s daughter, Edith, remembered Rockart in 1936 as “the man who probably knows more about the Capitol than anyone now living…. Mr. Gilbert many times said he never could have done what he did without Mr. Rockart.” Rockart worked with Gilbert on many prominent projects including the Woolworth Building in New York, the Virginia State Capitol and finally, the U.S. Supreme Court building which Rockart completed after Cass Gilbert’s death. The name that he insisted on having inscribed in the vestibule of that building is “John Rachac Rockart.”

Meanwhile, back in St. Paul, when the Capitol construction was finished, John Rachač Sr. was hired on as a full-time maintenance carpenter at the building and worked there until he retired at the age of 76 in 1925. In 1915, when Rachač was 66 years old, he had been hit by an automobile and his leg was permanently injured. The accident, however, did not stop him from working at the Capitol for another 10 years. When he died in 1936, his obituary in the Pioneer Press emphasized the fact that he had been forced to retire from his job at the Capitol ten years earlier by the leg injury. His working career had lasted some 64 years, from his apprenticeship at age 12 in Bohemia in 1861 to his retirement in 1925. Typical of a carpenter, he had worked on jobs as small as a shed for his C.S.P.S. friend, Vaclav Picha, to as large as the Capitol building and everything in between. Much of this work has been destroyed but we will have the Capitol and the Hill house as examples of the craftsmanship of John Rachač for many years to come.

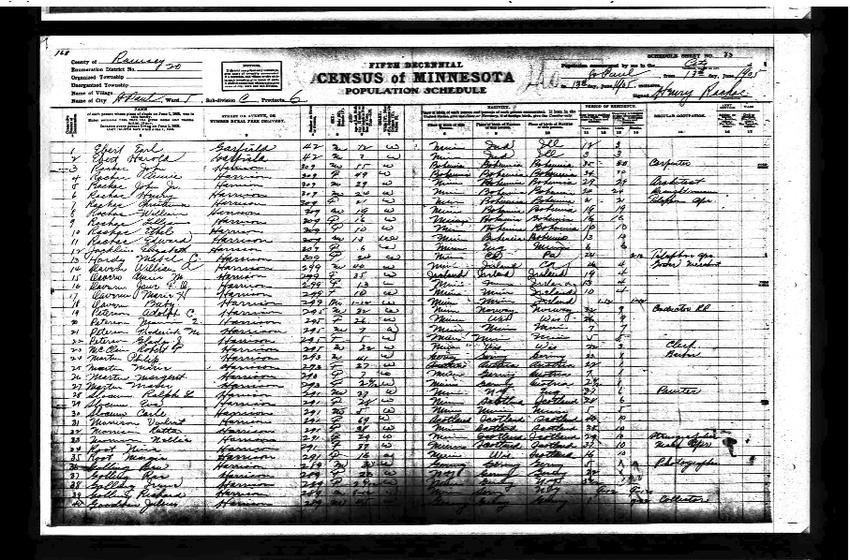

See US Census Data Sheet for John Rachac

"Mažice, (where the Rachač family lived since the mid-18th century) is a village and municipality in Tábor District in the South Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. The municipality covers an area of 5.51 square kilometres, and has a population of 129." - Wikipedia

Julie Kierstine, John Rachač's great granddaughter, returned to the family's home in Mažice during 2016. She discovered that two grand nephews of her grandfather, Jan and Vaclav, were living in the family home until 1948, when the Communist government confiscated the house and sent the brothers to forced labor, most likely in a factory. The building was used to store livestock and munitions. The brothers returned to Mažice, but could not keep up the house and it fell into disrepair. The surviving brother sold it to a Prague bussinessman who had it restored to it's original condition, as seen in the photos below. The family went to church in the nearby town of Zálší, where many of the family are buried.

Documents